When people hear the word “imbalance,” it often triggers alarm bells—especially in the context of international trade. But not all imbalances are detrimental; many are a natural consequence of economic dynamics. A trade “deficit” between countries of unequal size is not only expected, it’s a sign that trade is functioning as it should.

Consider two countries: one with a population of approximately 41.5 million, and another with over 340 million. The larger nation has a workforce, consumer base, and economy significantly greater than that of the smaller one. Naturally, it’s going to import more goods, simply because its people demand more of everything—fuel, food, manufactured goods, and raw materials.

The notion that trade should be balanced dollar-for-dollar between countries, regardless of their size or economic structure, misunderstands the basics of supply and demand. Larger countries buy more. Smaller countries sell what they specialize in. That’s trade doing exactly what it’s supposed to: allowing each side to obtain what it needs most efficiently.

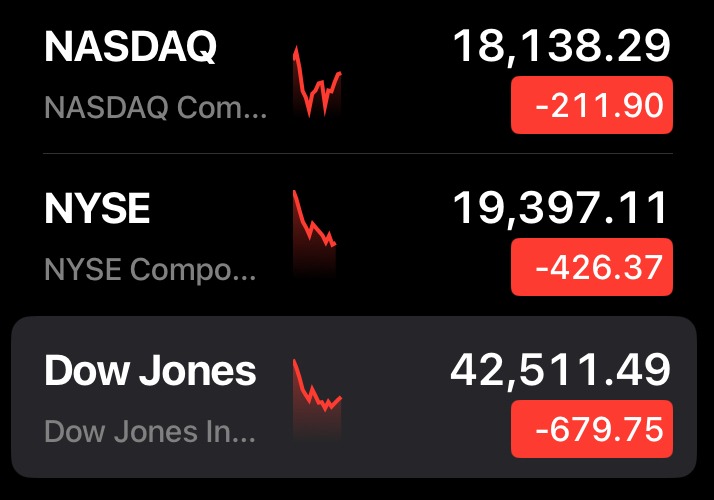

Imposing tariffs or demanding a “zero balance” with a smaller country doesn’t correct a flaw—it creates one. Tariffs often increase costs for domestic consumers and industries, who end up paying more for imported goods. In return, trading partners retaliate with tariffs of their own, hurting exporters. Nobody wins except a narrow band of protected industries—at the expense of everyone else.

Beyond population size, consider resources. Some countries have an abundance of energy, minerals, or agricultural goods. Others specialize in technology or financial services. No two countries are identical, and no healthy trade relationship is ever perfectly equal. That’s comparative advantage at work.

Insisting on a one-to-one trade balance ignores the reality that money spent on imports often flows back through other channels: investments, tourism, and capital markets. When we “import more than we export,” that doesn’t mean money is disappearing. It’s being reinvested, reflecting a strong and trusted economy.

Trade deficits can also reflect prosperity. People in wealthy nations consume more and travel more. They buy more goods and services—some domestic, some foreign. A deficit in goods can be offset by a surplus in services, or a surplus in investment income. Focusing solely on the trade-in-goods number is misleading at best.

Zeroing out trade “imbalances” is a political slogan, not an economic strategy. The real question isn’t who has the bigger number—it’s whether the overall arrangement leaves both countries better off. For most of modern history, the answer has been yes.